Originally posted – December 10th on nigeriahealthwatch.medium.com

By: Nigeria Health Watch

Chinonso Kenneth and Farai Shawn Matiashe (Lead Writers)

During Dr Laura Stachel’s postgraduate research on maternal mortality at Gambo Sawaba General Hospital (GSGH) in Kofan Gayan, Kaduna State, in 2008, she noticed a connection between the lack of energy supply and high maternal mortality at the health centre.

She also observed that critical procedures, caesarean sections, clinical operations, were being cancelled or delayed because of lack of power,” Dr Julie Yemi-Jonathan, Country Programs Manager of We Care Solar Nigeria said.

Stachel convinced her husband, a solar engineer, to build a small off-grid solar electric system, similar to a suitcase, and capable of powering the maternity ward at GSGH. The first of these yellow-coloured solar suitcases was installed in March 2009 at the facility in Kofan Gayan.

After her return to the United States at the end of her study, Stachel was inundated with testimonies from health workers at the Kofan Gayan Hospital and requests from other health centres. This inspired her and her husband to co-found We Care Solar in 2010, starting with the off-grid solar suitcases to provide renewable energy for maternity wards in health care centres.

The yellow suitcases

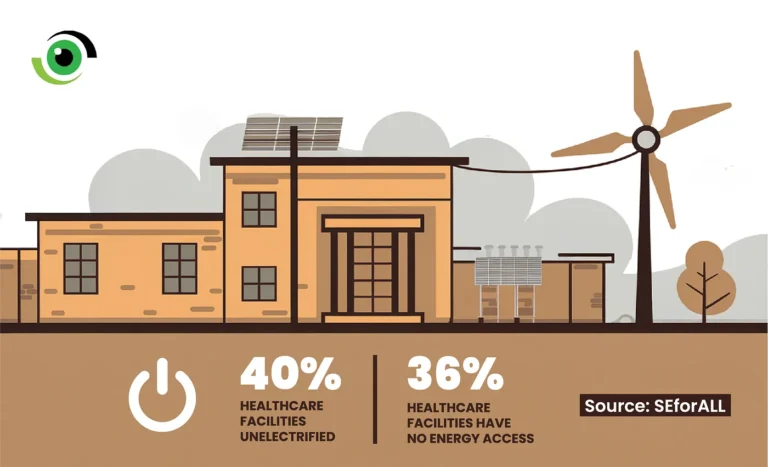

A report by Sustainable Energy for All (SEforALL) shows that 40% of functional primary healthcare centres (PHCs) in Nigeria lack access to electricity. Power cuts are frequent in Nigeria. In 2024 alone, the national grid collapsed over eight times, leading to nationwide blackouts.

According to Nurse Mary Umoru, who works at the Lugbe PHC in Nigeria’s capital city, Abuja, birth attendants used the light from their phones to take deliveries. “There were points where we used candles,” she said, noting that rechargeable lamps often fell due to health workers having to either hold it in their hands or with their mouths making them likely to fall. “Personally, I’ve destroyed two phones because of using my phone torch,” Nurse Mary said.

The solar suitcases, also called ‘yellow suitcases,’ come with a 12 volt, 20Ah lithium battery, a solar panel, four high-efficiency LED lights, two 12V DC accessory sockets, and two USB ports. They also include two rechargeable headlamps, two expansion ports, a fetal Doppler and infrared thermometer with rechargeable batteries, and a battery charger.

Through its Light Every Birth initiative, We Care Solar has installed around 580 solar suitcases in labour wards across 560 frontline PHCs, reaching a catchment population of five million women in the FCT, Kebbi and Bauchi states.

Mrs Princess Egbo, who gave birth during the early hours of Wednesday, November 13, 2024, at Lugbe PHC in Abuja, said the solar suitcase came to her rescue as power was unavailable at 1:51 a.m. when she went into labour.

“Just a minute before I went into labour, they took the light, but the solar came up, and I was so excited because I was already saying I wanted to give birth in the morning so that I wouldn’t have any issues. I didn’t know there was solar,” Egbo said.

“We want it to be extended”

The solar suitcases are meant to power only labour and maternity wards. Nurse Esther Adepoju of the Kuchingoro PHC, also in Abuja, said they would like the solar power to be extended to other essential units in the PHC, such as the outpatient department and post-natal ward.

However, Dr Yemi-Jonathan noted that the solar suitcases aim to ensure safe birth deliveries for women by lighting up labour rooms and maternity wards. “It’s not there to power the whole facility. It’s not there to address all the power issues. Some have asked why it can’t power the centrifuge. Why can’t it power the incinerator? These are critical parts of the hospital, but it is just here for timely and efficient emergency obstetric care.”

Abubakar Mohammed, a health system expert and management consultant with the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Nigeria, noted that while We Care Solar’s niche focus and model are effective in reaching many PHCs at low cost, other critical sections in PHCs need to be powered.

Climate change and lack of infrastructure affect Zimbabwe’s

Zimbabwe, like Nigeria, is also faced with the challenge of power shortages. However, innovations in renewable energy are proving to be lifesaving in maternity wards. In eastern Zimbabwe, Ndaizivei Makuyana was blessed with a healthy baby girl at an off-grid solar-powered clinic in the early hours of Saturday, September 14, 2024, just two weeks after celebrating her own birthday.

The 19-year-old mother vividly remembers holding her baby in a well-lit maternity ward at Hakwata clinic in Chipinge, about 510 kilometres from the capital Harare, for the first time. “It was a joy. My sunshine,” she said.

Ndaizivei is one of the 11,653 people from this remote community — not connected to the country’s electricity grid — who rely on the off-grid solar power plant. “I went to the clinic the previous day at night when I started feeling labour pains in the company of my husband and uncle. The lights were on, and unlike my mother, I did not bother looking for a candle or a torchlight,” she said. “Luckily, I had no complications. I had a normal delivery around 4 am.”

Back in 2005, Ndazivei’s mother delivered her baby at the same clinic in a poorly lit maternity ward. They used torchlights and candles in the ward and the entire clinic, but this changed in 2015 when solar lamps were installed at the clinic, says Maxwell Chitawala, a nurse in charge at Hakwata Clinic.“But we could not power fridges to cool vaccines or plug other critical devices,” he says.

In 2022, a small solar system was installed to power the whole clinic, including fridges for vaccine storage, laptops for data capture, and other devices used at the clinic. However, they occasionally experienced some challenges. “The system became weak during cloudy days,” Chitawala noted.

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), in partnership with the Rural Electrification Agency (REA), has set up a 200 kilowatt (kW) solar mini-grid in Hakwata, located at the border with Mozambique in Manicaland Province. The mini-grid provides uninterrupted clean energy to a clinic, 80 homesteads, a school, and a business centre.

Before this, nurses at Hakwata asked pregnant mothers to bring their lighting, says Chitawala. “It was tough to tell these mothers to bring candles to the clinic given they could not even afford to buy [birth preparation items],” he says.

There are still some clinics where midwives use torchlights and cell phone lights in maternity wards across Zimbabwe. Even those health facilities connected to the main grid, like Chitungwiza Hospital, a referral hospital 25 kilometres outside Harare, are being switched off because of power shortages experienced across the country.

Zimbabweans endure daily power outages schedules lasting for more than 18 hours. This is because of low water levels due to the El Nino drought in Lake Kariba, Zimbabwe and Zambia’s main source of generating electricity.

Equipment at the Hwange Coal Thermal Power plant has also aged, plunging the country into a power crisis. Chitawala says lighting is vital, particularly after birth when an umbilical cord is cut and clamped to prevent bleeding. “Blood Pressure machines are now digitized, and they need power. Oxygen concentrators also need electricity to assist babies after birth. When doing the umbilical procedure, one needs light.

“We were limited because we did not have electricity. You also need light to monitor bleeding or even frowning. Too much frowning by a pregnant woman during birth means the midwife needs to act fast. All this is possible when there is proper light,” Chitawala said.

To help reduce maternal mortality, Zimbabwe rolled out shelters for pregnant women at health facilities across the country, including at Hakwata Clinic. Those who live long distances from the clinic come and stay at the facility during their last six weeks of pregnancy, and their lives are made easier by the renewable energy from the off-grid solar plant.

The solar power plant runs on lithium batteries and has a lifespan of 15 years, and the consumers pay $0.11 per 1 Kwh to maintain the grid. “We use the electricity to pump water for expecting mothers to use for bathing and cooking. They use it to charge their cell phones. This encourages them to come and stay here and deliver safely,” Chitawala said.

Abubakar Mohammed noted that the hospitals’ current reliance on national grids as their main source of energy is not sustainable, due to the ageing power infrastructure and poor maintenance culture in Nigeria and Zimbabwe. “ The major focus should be solarisation as against the PHCs relying on the national grid [as the main source]; let it just be renewable,” he said.

In Nigeria, Mrs Egbo and her month-old baby are back at the PHC for free routine immunisation. “Everything is going smooth here, and I love it, the light, everything”, she said.

For Ndaizivei, giving birth to her daughter in a safe and well-lit maternity ward, unlike her mother 19 years ago, is a blessing. “My grandmother named her Anashe, a Shona name that translates to ‘One with God’,” she said.